LAUREN EWING

LAUREN EWING is a sculptor and installation artist who also creates drawings, prints and photographs. Her art addresses the vast construct of material culture in relation to memory, desire and language. Many of her sculptures and installations are polyvocal simultaneously using image, object, space and unique electronic texts that are thematically provocative and richly poetic. Lauren Ewing has exhibited nationally and internationally in museum and galleries including Diane Brown Gallery, NYC; Castelli Graphics, NYC; Sonnabend Gallery, NYC; John Weber Gallery, NYC; the Hirshhorn Museum; The New Museum of Contemporary Art; the Decordova Museum; Storm King Art Center; the Kunstverein Ludwigsburg, Germany; Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedefabrik, Denmark; Interim Art, London; the Sydney Biennale, Australia and many others. Her work is in many private and public collections including the Metropolitan Museum, NYC; the Museum of Modern Art, NYC; Chase Manhattan Bank Collection; the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art; the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art; the Walt Disney Collection. Her public sculptures are located in many American cities including Seattle, Sacramento, Atlantic City, Denver and Philadelphia. Lauren Ewing currently has studios in New York City, Indiana and Provincetown.

LAUREN EWING RECENT WORK

ILLUMINATION & HABITATION

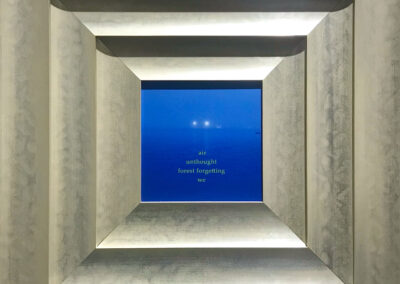

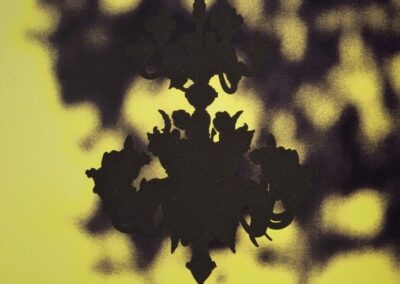

ILLUMINATION & HABITATION consists of four photographic images, each 36 x 36”, two sets of sculpture and one individual sculpture, all editioned. The two groups of work in the exhibition Illumination and Habitation are conceptually related. Both involve illumination and familiar aspects of domestic material culture, houses and chandeliers so that the work asks the eye and the mind to move back and forth between light and darkness, nature and culture, object and place, natural material (coal) and synthetic process. These are some of the parameters of technological society that perpetually interest this artist. In making Illumination and The Forest Ewing has made images that are gorgeous and contradictory, like life itself. In them it is difficult to visually separate nature and culture and therein to ask if those separations are truly possible today. The fragment of a tree at the edge of a forest has been softened so it recedes behind the sharp silhouette of a Venetian chandelier. The complex biomorphic tracery of the tree both precedes its cultural imitator, the chandelier, and merges with it in these collided images. At differing times of day and night the two images merge and separate themselves out from one another, a kind of visual dance, coming together and moving apart.

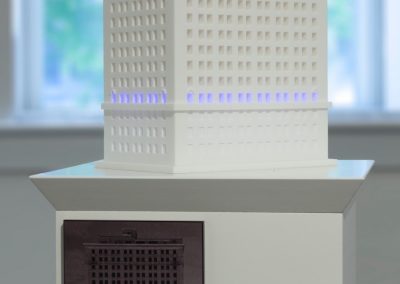

Common Houses (American pre-modern) is a collection of house types that are a part of social memory. It is this shared memory that creates a sense of belonging. As such these shapes and their respective proportions are thoroughly familiar to all of us. They are part of a vast vocabulary of the shapes of habitation that have been repeated millions and millions of times in American cityscapes before the 20th C. They are a part of our visual culture that we take for granted. These editions articulate that vocabulary of habitation. The three different editions vary between solid and hollow, dark and illuminated. Ewing made them in the scale of the hand to emphasize that the built environment is our creation and we are responsible for its effects.

She states, ‘Seeing the world around me, not the idealized theoretical position of Modernism, is where all of my work begins. I am a great admirer of the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Their documents of industrial and domestic typology are guides for seeing the world we live in. At this time in history we should be asking ourselves, can we balance the effects of human material culture with the limits of the natural world? These little collections are reminders of how vast and varied the built environment is and how central it is to human life. Two series will follow, Modern and Postmodern common houses.’

THE PROVINCETOWN AIDS MEMORIAL

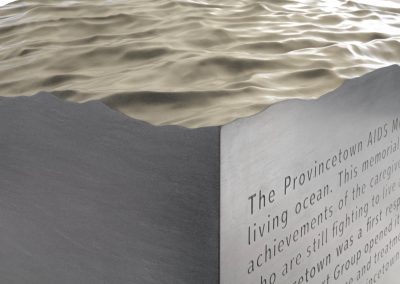

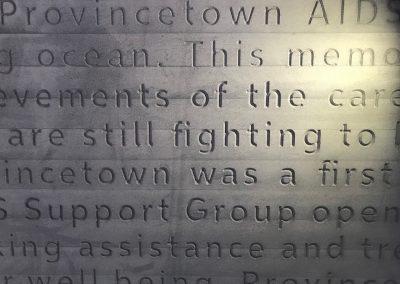

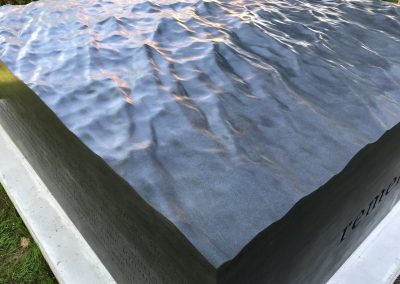

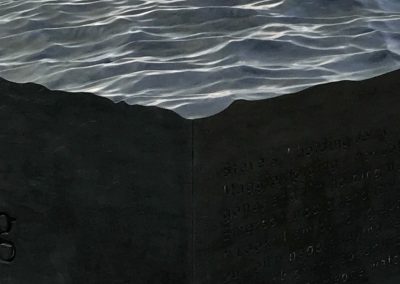

The Provincetown AIDS Memorial is located at Provincetown Town Hall on the lawn at the Ryder Street entrance. The Memorial will become part of the Town of Provincetown’s permanent art collection. The Memorial has been sculpted from 16.5 tons of carbon gray Quartzite, a stone strong enough to stand up through the freezing and thawing of New England winters and constant salt air. The stone was sculpted in Tuscany with the aid of CNC robotic stone milling equipment and then finished by hand.

The top of the square 9-by-9-foot piece reflects the rippling sea surrounding Provincetown. “This is one of the most inspirational views,” says Ewing, looking out to Cape Cod Bay from the deck of her Commercial Street home. “It’s beautiful, powerful, threatening and soothing. People look out at the sea to clear their minds. There is awe. It’s about how deeply humans can feel. It’s appropriate for the sobriety of the monument.”

Her own relationship to the epidemic is as a gay American who watched people go through pain, fear and loss. “The prejudice was heartbreaking,” she explains. “What people did here when the rest of the world was freaking out — they offered an open heart before they thought of themselves. P’town cares about being a caring community.”

COLONIAL HYBRID

COLONIAL HYBRID: When in June of 1989 the Nicholas Brown block front desk/secretary sold for $12,100,000 at Christie’s it became the most highly valued piece of American furniture in history. Ewing’s initial interest in how value is produced led her to major museums throughout the US where she observed and closely measured six Goddard and Townsend block front desk/secretaries from the 18th century, all of the same type and approximate date as the Nicholas Brown. Because at the time she was on the faculties of Rutgers and Yale she was given access to the collections at the Metropolitan NYC, MFA Boston, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Winterthur, Garvan Collection at the Yale Museum and drawings of the Nicholas Brown itself supplied by Allan Breed who was making the replacement replica for the Nicholas Brown Center at Brown University.

The artist focused on these pieces to explore questions about material culture, how it speaks, where it intersects with social history and how and why it is valued. An initial interest in the production of value by cultural mechanisms turned into an act of the production of value by the artist. Ewing performs a perfect translation, an inversion of signification. She takes a highly valued and exclusive icon of entrepreneurial power and familial continuity and transforms it into “Everybody’s Nicholas Brown” and the companion piece “Everybody’s John Brown”. As sculpture both of these pieces become instruments through which the viewer can speak, an instrument for the “giving of voice” to everyone.

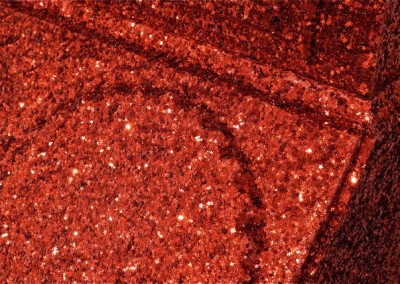

“Colonial Hybrid” is the 3rd piece in this series. To make it Ewing crunched all the measurements of the 6 Goddard and Townsend pieces to made a proportional hybrid. Covered with millions of tiny gleaming red stars the “Colonial Hybrid” is a popularized, spectacular object. Ewing made this final piece to draw attention to the role that material culture plays in the formation of collective social memory.