JOHN DUGDALE

JOHN DUGDALE (born 1960 in Connecticut) attended the School of the Visual Arts in New York City where he majored in photography and art history. In 1983 his photographic work was first presented in a solo exhibition at Vienna‘s Molotov Art Gallery. The show and the catalogue were curated by Christian Michelides, the founder of the gallery. Thereafter he started a successful decade long commercial career working for such clients as Bergdorf Goodman, Martha Stewart and Ralph Lauren.

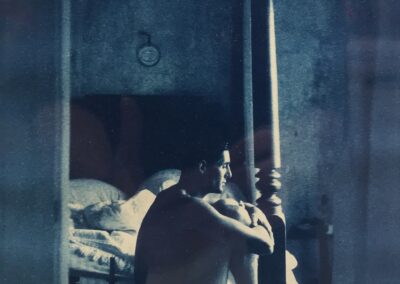

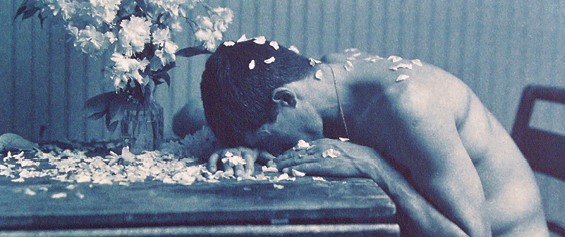

In 1993, at the age of 33, Dugdale experienced nearly total blindness due to a stroke and CMV retinitis, an HIV-related illness. He became completely blind in his right eye and lost eighty percent visibility in his left eye. He lost his remaining vision in 2010. This tragic event ended his successful commercial career, but he decided to persist in photography and started to explore techniques from the 19th century for fine art photography, using friends and family as assistants. Since then Dugdale has worked with large format cameras, creating cyanotype prints, platinum prints – using the albumen process which became the dominant form of photographic positives from 1855 to the turn of the 20th century. His sensibility for bygone techniques emphasizes the poetics of his work and the transcendence of time and place, seemingly transporting the imagery to a different era. A quote of the nearly blind photographer: “The mind is the essence of your sight. It’s really the mind that sees.”

Dugdale has exhibited in over 25 solo shows in galleries all over the world. His work has been seen in group shows at the Miami Art Museum, at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield; his photographs are included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Whitney Museum in New York as well as in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The artist has been inducted into the Royal Photographic Society in Bath and he spoke on BBC, NPR, at universities and other public and private events where he continues to discuss 19th century photographic processes as well as his own aesthetic point of view – answering questions pertaining to what it means “to see.”